Misconceptions in Commercial Real Estate – The Truth About High IRR Return Projections

I recently encountered a buyer who was planning to acquire a

rather old apartment building, intending to renovate it entirely, and then to

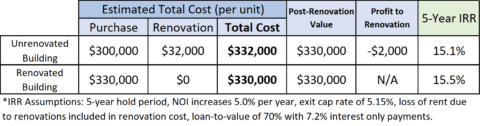

re-lease it at higher rents. The buyer had estimated an IRR (Internal Rate of

Return, equivalent to the annualized return on investment) of 15.1% per annum

over a five-year holding period, which is relatively attractive for value-add

projects of this type. However, after learning more about this investment

project, I had doubts about the IRR result and the proposed purchase price.

After analysis, I recommended the buyer to renegotiate with the seller before

investing.

professionals generally will not base commercial real estate pricing solely on

IRR, as it can too easily lead to overpaying for property. Below I introduce

two methods commonly used by professionals to quickly evaluate the investment

value of commercial real estate projects and avoid the pitfalls of misleading

IRR estimates. An apartment building is used as an example here; however, the

same methods can be used for virtually all types of commercial real estate,

including industrial, office, retail, hotel and others.

Method

One: Compare with Already Renovated Real Estate

Buying or Selling a Home? We Can Help

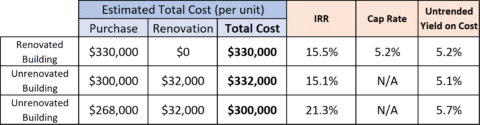

The buyer asked for my help, and after researching the local

market, I discovered another apartment building located in the same area that

was very similar to the one he planned to purchase. Both were of the same

vintage, had similar unit layouts, and were generally comparable. The only main

difference was that the building I found had recently been renovated and had

already been fully re-leased at current market rental prices. Although, the

asking price per unit of the renovated apartment building ($330,000 per unit)

was higher than the per unit price the buyer had negotiated on the unrenovated

building ($300,000 per unit), it was estimated that renovations would cost

$32,000 per unit, thus the total cost to purchase and renovate the unrenovated

building would actually be slightly higher than the cost to simply purchase the

already renovated building. As both buildings would likely have similar market

values post renovation, it follows that the total cost to purchase and renovate

($332,000 per unit) would likely be higher than the market value after

renovation ($330,000 per unit). In other words, the renovation itself would be

a losing investment.

This begs the question, if renovating the building results in

a loss, how did the buyer estimate such a high IRR of 15.1%? The answer is that

his IRR return estimate resulted from the combination of optimistic future rent

growth assumptions and the effect of high leverage, but not from the planned

renovation. Thus, it follows that, assuming these assumptions and leverage

projections are accurate, if the buyer were instead to acquire the already

renovated apartment building, the same high market rent growth and high debt

leverage would result in an even higher IRR of 15.5%, without the trouble of

renovating.

Because renovation carries risks, higher returns are

generally required for a renovation project. In the above example, however, the

IRR was lower for the renovation project. When this happens, it is likely

because the purchase price of the unrenovated apartment building is too high.

At the same time, the estimated rent growth rate was rather optimistic (perhaps

overly so), resulting in an IRR that still appears attractive, despite incurring

losses on the renovations. Thus, when estimating a purchase price, it is

important to temporarily ignore IRR, and focus on the total project cost.

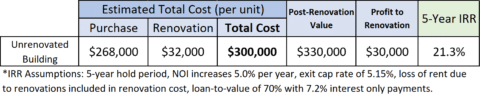

If it were possible to purchase the unrenovated apartment

building for just $268,000 per unit, the total cost including renovation

expenses would be $300,000 per unit. As the market value post renovation is

expected to be $330,000 per unit (before considering any market rent growth),

undertaking the renovation would result in a 10% increase in value. Thus, by

most investment standards, it would be an attractive investment property with

the potential to add value through renovation.

Using this total cost comparison method to calculate return

on value, results are unaffected by assumptions about future rent growth or

potential loan leverage. If rent growth and leverage costs deviate from initial

assumptions, this will still not affect the increase in value that results from

successfully executing the renovation. However, IRR is different. In the above

scenario, assuming a purchase price of $268,000 per unit, the resulting IRR

would be 21.3%. However, if the rent

growth and debt leverage assumptions turn out to be overly optimistic, actual

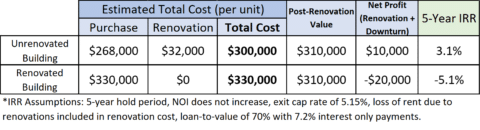

IRR results will be much lower. For example, assume a market downturn is

encountered after purchase, resulting in a drop in market value to $310,000 per

unit post renovation, followed by flat rent growth.

If the already renovated building had been purchased for

$330,000 per unit, the market downturn would result in loss of $20,000 per

unit. However, if the unrenovated building had been purchased at a total cost

of $300,000 including purchase and renovation costs, the renovation might still

achieve a $30,000 per unit increase in value. Combined with the $20,000 loss

due to the market downturn, this would result in a net profit of $10,000 per

unit. Regardless of which building is

purchased, both would incur similar losses due to the market downtown, however

undertaking the renovation adds value independent of swings in the market.

Comparing unrenovated real estate with similar, already

renovated real estate is a common pricing method for value-add projects, but

this method also has many flaws, including:

1. It

can often be difficult to find already renovated projects that are similar, or

sales price data may not be available.

2. Even

if some sales price data is available, it may not reflect market prices.

3. Commercial

real estate generally places more emphasis on the valuation of cash flows.

Therefore, professionals in the US commercial real estate

industry often tend to place more emphasis on method two below.

Method

Two: Estimate the Untrended Yield-on-Cost

The untrended yield-on-cost is

commonly used to price renovation projects.

It is similar to the capitalization rate (cap rate), however different

in important respects. For real estate projects that do not require significant

renovation, the cap rate is commonly used to estimate or validate market value.

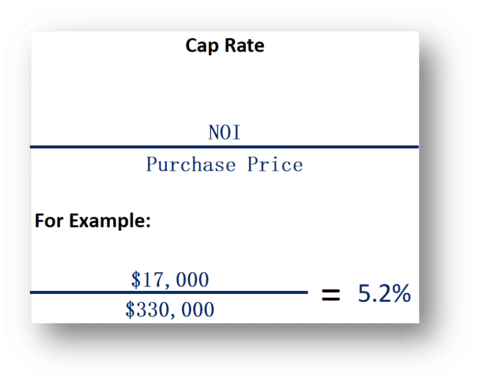

The cap rate of the investment project is estimated by dividing annual net

operating income (NOI) by the purchase price or market value of the project.

This project cap rate is then compared to the cap rate for similar properties

on the market, or it is compared to “market cap rates” reported by real estate

companies.

In the above example, the cap rate of the renovated apartment

building was 5.2%. If it is assumed that the market cap rate was also 5.2%,

then the price may be considered reasonable. If instead the market cap rate

were lower than 5.2%, this would indicate that the renovated apartment building

may be priced below market, i.e. at a discount. Nonetheless, it should be noted

that the cap rate of a specific investment project and the market cap rate are

somewhat subjective judgments, and the characteristics of the project (such as

maintenance condition, age of the building, location, length of lease

contracts, tenant quality, etc.) will generally result in variance in the cap

rate. Therefore, the cap rate tends to be a quick and dirty method and cannot

completely replace more in-depth analysis, especially for non-standard

projects.

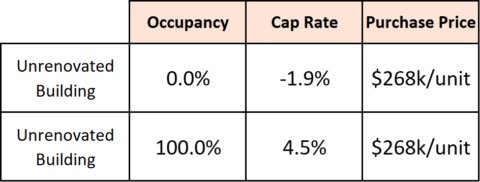

However, for value-add projects, the cap rate is generally

meaningless, as it does not consider renovation costs or the increase in rents

that results from the renovation, among other things. As such, it does not

reflect the potential of value-add projects and will not produce accurate value

estimates. For example, a completely vacant building will have a cap rate of

zero or even less, due to carry costs such as property taxes, insurance,

maintenance, etc. Conversely, if the exact same building were fully leased out,

its cap rate could be relatively high. However, assuming both are value-add renovation

projects, the pricing is unlikely to be affected much by the current vacancy

rate, i.e. they will be sold at similar prices, because their value is not

derived from existing net cash flows, but rather determined by the potential

future cash flows following renovation.

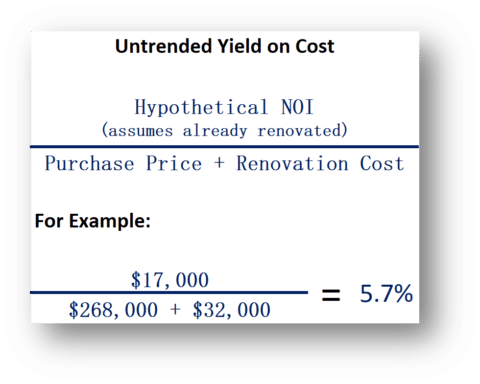

To address issues with the cap rate, one method industry

professionals typically use is to estimate the untrended

yield-on-cost, which is calculated similarly to the cap rate, but with some key

differences. The untrended yield-on-cost assumes that

the project has already been renovated, then estimates the potential

unleveraged annual NOI achievable based on hypothetical market rents for the

post-renovation building at the time of purchase, and then calculates the ratio

of this hypothetical NOI to the total cost of the project, i.e. the cost to purchase and renovate the project.

In reality, because applying for construction permits, evicting tenants, construction, leasing, etc., all take time, the NOI achieved

after renovation will not only increase as a result of the renovation, it will

also fluctuate with the rental market and other factors. However, in order to

more clearly differentiate the value added by renovation from any assumptions

about future rent growth in the market, it is recommended to calculate the untrended yield-on-cost based on hypothetical current

market rents at the time of purchase, even though renovations may not be

completed until much later.

For projects that do not undergo renovation, the cap rate and

the untrended yield-on-cost will always yield the

same results. However, for value-add renovation projects, the untrended yield-on-cost is generally required to be

substantially higher than the market cap rate. In the above example, the market

capitalization rate of the renovated apartment building is 5.2%, indicating

that purchasing an already renovated apartment building should be able to

achieve a NOI equal to 5.2% of the total purchase price. However, if purchasing

the building that requires renovation, then NOI equal to at least 5.7% should

be achievable, calculated as a percentage of the total cost to purchase and

renovate the building.

This additional 0.5% of NOI represents the value added by

renovation. Commercial real estate is commonly priced based on NOI, and this

0.5% is equivalent to approximately 10% appreciation in market value. This

appreciation is independent of future market rent increases or debt leverage.

It only reflects the appreciation brought by renovation. In the above example,

only if the cost to purchase and renovate the apartment building is $300,000

per unit or less, can an untrended yield-on-cost that

is 0.5% higher than the market cap rate be achieved.

It should be noted that the percentage of required additional

NOI will vary depending on the extent of the renovation and the market cap

rate. In markets with cap rates around 5%, investors will typically target an untrended yield-on-cost approximately 0.5%-1.0% higher for

a renovation, and about 1.0% higher for more extensive renovation or ground up

construction. However, when the market

cap rate is higher, these percentages will generally increase

proportionately. For example, a project

with a 10% market cap rate may require an 11%-12% untrended

yield-on-cost.

Thus, it can be seen that estimating the untrended

yield-on-cost can help show the true value added by renovation and help us to

accurately price commercial buildings in need of renovation. Conversely, a high

IRR may just be the result of unreasonable rent growth assumptions or high debt

leverage assumptions and can potentially mislead buyers and investors to

overpay for commercial real estate and pursue unprofitable renovation projects.